A primer on aerial photography

by Randy Hanna

I started flying during high school and have been flying ever since. In the Army, I had an opportunity to fly helicopters in an elite aviation unit and learned countless lessons. Although I still enjoy flying, if given the choice, I would rather be photographing from the air than flying—which is a major departure for me. This primer is based on both a view from the cockpit as well as that of a photographer, and specifically for a helicopter as a shooting platform.

There is no doubt that aerial photography is challenging, demanding, and frustrating—unless you have an understanding of the basics. Once understood, you will find yourself wanting to fly just about every chance you get; I know I certainly do.

A VIEW FROM THE COCKPIT

The cockpit, quite frankly, is a very busy place. It is where failure to pay attention to detail can lead to catastrophic results. That said, a well-executed aerial shoot can be not only successful but also exciting. The job of the pilot is to balance his workload in such a manner that is complementary to your shooting requirements. To do so, he or she has to have certain things from you, the photographer, right from the start.

PRE-FLIGHT PLANNING

I believe that the flights which yield the fewest number of high quality images are largely due to poor planning, no planning, or ineffective communication. If you jump into the aircraft and say ‘let’s go,’ when you should have previously discussed objectives and done some route planning, you will get a scenic flight rather than a photo flight. It is your responsibility to share your objectives and shooting priorities with the pilot. You should also make use of photography planning tools such as The Photographer’s Ephemeris or Sun Seeker and integrate these into your discussion about shooting directions in order to handle shadows and light. The best approach is to communicate your desires to the pilot several days in advance, so he or she can do the necessary flight path planning, check on local restrictions, assess weather conditions, and Notices to Airmen (NOTAM) for last minute issues that could impact your flight.

COMMUNICATING WITH YOUR PILOT DURING THE FLIGHT

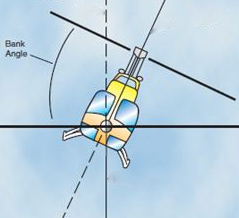

As I said before, it can be busy up front. When I am flying, it is not uncommon for me to be listening to three or four radio channels concurrently plus communicating with the passengers, and oh, yes, flying the aircraft. Don’t be alarmed if the pilot asks for no talking until they get beyond the traffic control area or the congested area. During your safety orientation would be a good time to work with your pilot on desired instructions; in other words, make sure you both are on the same page when it comes to telling him or her how to position the aircraft. Yes, it is your responsibility to tell the pilot how you want the aircraft positioned. One example of this necessary communication would be working together to keep the rotor blades out of the photo. Both of you have a part to play in this. You can rotate the camera up and down; however, your composition may dictate a camera position in which the blades could be in the top of the frame. By using a rehearsed command to the pilot such as ‘tips up’ or ‘bank left / right’ will tell the pilot that he or she needs to rotate the aircraft to the right (or left) along its center axis, thus tipping the blades out of the photograph. Working together and using common commands, this is easy to do.

SHOOTING POSITIONINGS IN THE AIRCRAFT

I always fly in a doors-off configuration. If I have to shoot through the window, I’m really not interested in flying. In aircraft that will support it, I prefer to position all shooters on the same side of the aircraft. This simple trick reduces orbit time around any given point of interest. If shooters are working on both sides of the aircraft, you will find the aircraft pivoting around a point to the left and then to the right to ensure everyone gets their shots. With everyone on one side, it only requires a single orbit, and then you are off to the next location. This positioning will save you lots of time, and time is money with these machines.

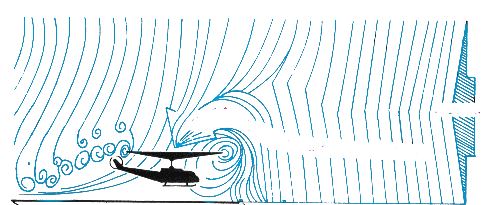

Helicopters, in particular, have a more pronounced slipstream than many other aircraft. As the aircraft moves through the air, the airstream moves across the fuselage in many different directions.

As long as you don’t penetrate this slip stream, you are just fine. As soon as you penetrate the slip stream, you will feel the full force of wind associated with forward flight. When you find it difficult to hold your camera in one position, it is a sure sign that you are in the slipstream. Simply lean back into the aircraft and you will be fine.

DOORS-OFF FLIGHT CONFIGURATIONS

A typical configuration for an MD500 is with both photographers shooting on the same side.

By far, my first choice when doing aerial photography is the Eurocopter A-Star B350. When shooting from the A-Star, the best seat in the house, as far as I am concerned, is tethered to the aircraft using a harness and sitting on the floor directly in front of the rear seat.

NO SECOND GUESSING THE WEATHER

When I was flying in the Army we had a saying: ‘There are old pilots and there are bold pilots, but there are no old and bold pilots still flying.’ Any responsible pilot will always put the safety of the mission first. This often means making the hard weather calls for the client. Pilots want to please their clients, but sometimes the lines between marginal weather and safe flying can become blurred. For example, if you receive a call in which the pilot tells you that the weather is marginal but we can probably still fly, follow your gut and make the decision to fly another day.

CLOTHING PREPARATION

We all know what wind chill is, so think about this: when you are flying with the doors off, you will be subject to wind blowing by you at hurricane forces as you transit from one location to another. Depending on the aircraft, your wind speeds could range between 90 and 140 knots (100-150 mph). Dress accordingly to make your flight enjoyable and successful. First up, gloves are critical and considered must-haves. Good gloves with gripping texture on the fingers will do the trick. The thickness of the gloves will depend upon the outside air temperature. If you are sitting on the floor with your feet on the skids, you also will need solid wind pants to cover your normal pants. It is critical that these wind pants not be loose-fitting. Remember, you will be exposed to some serious wind speed. I personally use the Arc’teryx wind pants and I often tape the bottom of each leg with gaffers tape. A good shell with a base layer underneath will keep your upper body toasty during the flight.

Camera straps are mandatory. In addition, there can be nothing loose in the cabin that could find its way into the tail rotor. As a pilot, I can do without many things and still fly quite well; however, a missing or broken tail rotor is not one of them.

Eye protection is another piece of personal protection that is often overlooked. I have found that sunglasses are a nuisance because I end up fighting them to deal with changing light. I now just use a pair of clear shooting glasses that are the wrap-around design, again with a strap.

With basic preflight information out of the way, it is time to turn our attention to camera preparation and shooting techniques.

FOCUS

Shooting from the air almost always means you are shooting at infinity. Because most lenses focus differently when it comes to infinity, it is critical to pre-focus your lens before getting into the aircraft. Set your camera on manual focus, pick an object in the distance with lots of contrast, and set the focus. Verify this setting by zooming in on the image using the playback screen. Take extra care NOT to move or touch the lens, thus changing the focus point. Once the infinity focus is confirmed, use gaffer tape to hold the lens at the infinity focus point (this is best done as a two-person exercise). You are now locked at your infinity focus point. Again, it is critical that you disable all auto focus actions.

LENS HOOD

During your safety briefing your pilot will ‘lecture’ you on the importance of NOTHING coming loose from the aircraft and potentially hitting the tail rotor. With the tail rotor perfectly balanced and spinning at nearly the speed of sound, it is easy to understand how even the smallest object coming in contact with the rotor could result in a non-recoverable event. I don’t care how securely your lens hood is mounted, it is not secure enough to overcome the force of the air moving across the side of the aircraft at near hurricane speeds. In addition to the tail rotor risk, a vortex will form inside the lens making it very difficult to hold in a steady position. Therefore, REMOVE your lens hood before you get in the aircraft!

SHUTTER SPEED

In a helicopter you must overcome two things regarding shutter speed. First is the inherent vibration of the aircraft, and second is wind speed. All helicopters are vastly different when it comes to vibration. While modern lenses with vibration reduction will help while you are on the ground, I have found that they are of little use in the air when trying to overcome the vibration.

One tool that can help with vibration is a two or three axis gyro stabilizer such as the one made by Kenton. These gyros normally mount to your camera via a bottom plate and are extremely effective. The downside to these gyros is their weight—three to eight pounds!

Your forward airspeed will generate wind blowing across the side of the cockpit and even more so if you are on the sitting on the skids. Based on years of flying, I have settled on a shutter speed of 1/1250th second as a minimum standard. This seems to be my sweet spot and is now my ‘go to’ minimum shutter setting. If supported by your camera, you should consider using the auto ISO function to help keep your shutter speed at or above the 1/1250th sec setting with changing light conditions.

DEPTH OF FIELD

Operating at a focus point of infinity, your need to use a high depth of field is often minimized. I usually try to use an aperture that is closest to the sharpest, while balancing the need to support the higher shutter speed. I think nothing of shooting at ƒ/4.0 or ƒ/5.6 if I can’t reach my desired ƒ/8.0 due to limited light. Remember, you are shooting at infinity so shutter speed is far more critical than ƒ-stop.

COMPOSITION

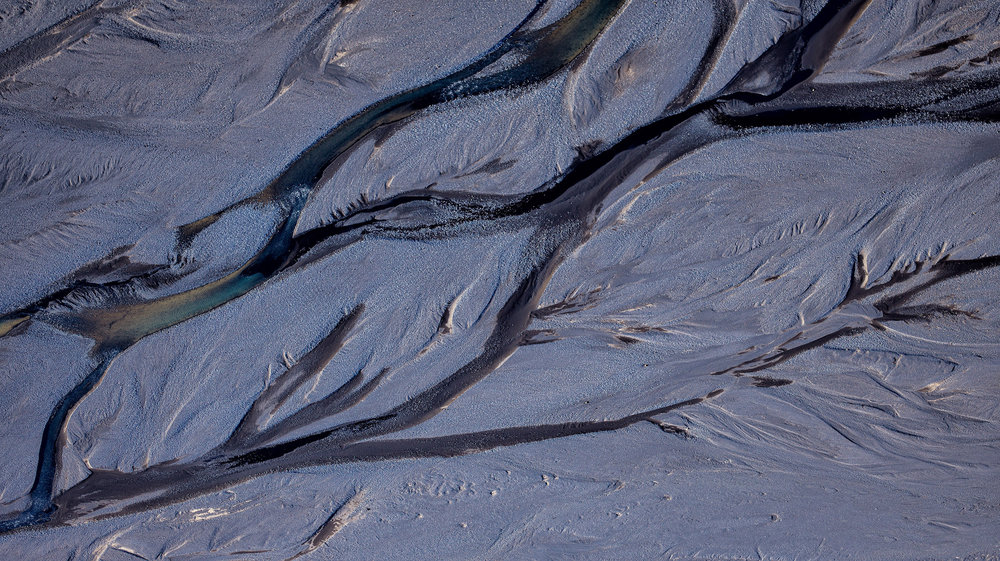

With all of your camera settings locked in, it is time to start concentrating on your aerial composition. Things will look dramatically different from the air than on the ground. At first you likely will be overwhelmed with the sensation of deciding where to shoot. Remember all of that pre-planning we previously spoke of? Well, this is where it pays off. Keep in mind that the perspective from the air will be different. My suggestion is to always look for lead-in lines. Try to find symmetry in the geometric nature shapes that will be more evident from the air. Keep in mind that you are shooting in order to take your viewers on the same journey that you are experiencing.

Now, go get this done and enjoy capturing a view seldom seen by most. Enjoy the aerial images from Iceland below.

View Post on Original Blog

https://muenchworkshops.com/blog/aerial-photography-tips-randy-hanna