By Sivani Babu

A couple of years ago, I found myself sitting shoulder-to-shoulder in the back office of a bookstore with celebrated author Tim Cahill — a founding editor of Outside magazine — and seven other writers. For nearly an hour, they picked apart a story I had written. When we were done, we moved on to the next piece. Through it all, there was only one rule: The author of the story was not allowed to speak during the critique. It sounds like a nightmare, right?

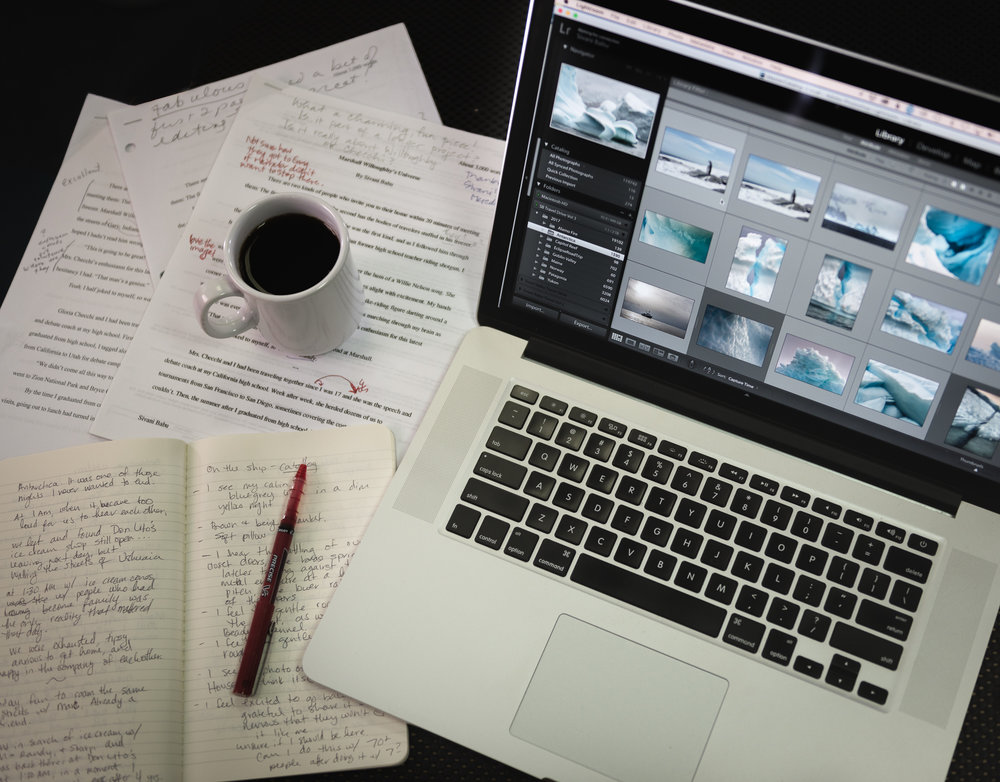

As a photographer and a writer, it is interesting to observe the different roles of critique in both disciplines, and the more I discuss those differences, the more convinced I am that too many photographers are missing out.

Writers work with editors — not just professional ones, but peers who fill that role as a story develops. We talk about “killing our darlings”— our favorite characters, our clever lines, our seemingly brilliant scenes, and sometimes our entire books. And we seek out opportunities to sit in rooms and listen to strangers deconstruct what took us days, weeks, months, and years to craft. At all levels, critiques are accepted as part of the writing process. But for photographers, particularly for those of us who did not go to school for photography, critique doesn’t seem to be as intrinsic to the process. We seem to be less likely to share our work in places where it will be critiqued. When we do share, we rarely share the images that we know didn’t work, preferring instead to show our favorites and our best. And, on the flip side, when a photographer seeks out thoughtful feedback, too often we don’t fully engage, choosing silence or platitudes over constructive criticism. The differences also go beyond informal interactions. When I am writing a story for publication, there is substantial back and forth between myself and an editor. This is essentially a form of critique. The process starts with the story idea, then continues with submitting the first draft, followed by feedback and revision. Usually, I go through between one and three rounds of revisions with the editor.

For photography assignments, however, the most contact I have with an editor is in the planning stages. With a few notable exceptions, after I’ve shot the story, I submit photos and wait for them to appear online or in print. It wasn’t always this way though. Not long ago, the feedback loop that I rely on as a writer would also have been there for me to rely on as a photographer. More publications had photo editors who worked with photographers at all stages of an assignment to create the best imagery possible, and if we look back at magazines and newspapers of that era, we can see the difference that the process made. To be sure, opportunities in photography to give and receive constructive criticism do exist, but they are not as ubiquitous as they are in writing and when they do arise, we frequently let them pass us by. Why is that? Why is critique less institutionalized in photography? And why, when the opportunities for critique are available, do we fail to grab them in a meaningful way? I can’t offer a definitive explanation. The digital age has had a dramatic impact on the art and industry of photography, and those changes are a major factor, but they don’t fully explain our individual responses to critique. The most common explanation is emotion. We are emotionally attached to our work. We put time and energy into creating images. We might travel for days and endure difficult conditions to capture that single moment when everything comes together. All we have to show for this effort are our photographs, and we’re proud not just of the millions of pixels we recorded, but also of ourselves for being there. So, the idea that someone might have something negative to say about our images, especially the ones that we consider our best work, can be disheartening. Even when coupled with constructive suggestions, critiques can feel personal. It’s just easier to avoid them altogether. There are other possible reasons as well. I’ve heard the saying, “You’re only as good as your weakest photo,” thrown around in photography circles with some frequency. It’s not hard to see how that might prevent people from sharing images they see as weaker for fear of others thinking that’s the best they can do. And I’ve also heard photographers dismiss the benefit of constructive criticism outright. “Personal style,” they say, “can’t be critiqued.”

Each of these reasons probably resonates with someone, and there are others that I haven’t considered. But whatever the reason, there’s a more valuable question to ask: What are we missing out on by foregoing critique? That one I can answer: opportunities. We’re missing out on opportunities to learn from one another; opportunities to consciously develop our own style instead of falling into it haphazardly; opportunities to become better observers; and opportunities to grow as photographers. A photograph is every bit a form of communication as words on a page. An image tells a story, but unless we are listening to how others perceive the story, we can’t know if we’re communicating effectively — if we’re telling the story we intended to tell. And if it seems like it’s easier for writers to accept critique, that’s probably because it is. Because for most of us, writing and critique have been intertwined with the concept of growth since we wrote our first essays in elementary school. Relearning that lesson in a photography context is both a difficult and worthwhile endeavor.

Back in that seminar with Tim, something wonderful happened when I wasn’t allowed to respond to the critiques: I stopped trying to respond to the critiques. Instead, I took in what everyone said without getting lost in any one comment. I became the fly on the wall as people talked about a story. That the story was mine became less important. And when I disagreed with a critique, instead of explaining myself outwardly, I had to turn inward and examine why I disagreed. As a result, a more cohesive articulation of my writing style emerged. Isn’t that what we also want from our photography? So, this is my challenge to everyone, including myself: Seek out meaningful critique of your photos. Start a conversation about an image that didn’t work, share an image about which you are uncertain, or put your best work out there and welcome the lesson if it turns out not to be perfect. Put yourself out there. Then sit back and see what happens when you become the fly on the wall. And if you’re on the other side of a Facebook post, or an email, or a face-to-face question, engage in the process and give thoughtful, detailed feedback — no emoji and no single-word responses. You won’t just be helping someone else out. As a writer and a photographer, I’ve learned so much more about myself and my own work by viewing and discussing the work of others.

All of this might seem uncomfortable at first, but do it anyway. Because on the other side of that discomfort there just might be a better image.

View Post on Original Blog

https://muenchworkshops.com/blog/the-importance-of-critique